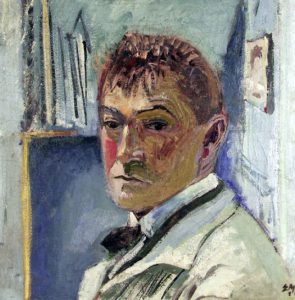

Ernst and Sasha Morgenthaler, painted by Ernst Morgenthaler.

“Laughter and Tears in Equal Measure”1

Steffan Biffiger

Ernst Morgenthaler was born in rural Kleindietwil in the Lower Emmental in 1887, where he spent his childhood and adolescence. His long-term friend Hermann Hesse described young Ernst from a photo taken around 1892:

“The family photo depicts the painter’s parents and their five children. One of Ernst’s brothers, who was a passionate drawer, appears particularly alert and talented but died at the age of sixteen. The father sits in dignity, like a sovereign amongst his people, by his side the mother gentle and humble; young Ernst, however, sits on the right with his mouth open, fat and naïve, healthy and somewhat dozy, completely unaware of the possibility that he might ever grow up to be anything other than a stolid, healthy and happy peasant boy.”2

His father Niklaus Morgenthaler, scion of a house of peasants, was a railway engineer at the Langenthal-Huttwil train company; he went on to become Bernese Regierungsrat (senior civil servant) and the family moved to Bern in 1897. In 1903 Niklaus was voted into the Swiss Council of States. Every-day life was characterised by work and there was little time to spare for cultural activities. In Ernst Morgenthaler’s own words: “There was no muse beside my crib to show me the right way. She did appear one day, but that was quite late—a real Bernese muse. She only opened her fat eyelids when I was in my late 20s.”3 After several false starts he joined Cuno Amiet at Oschwand in 1914 as a twenty-seven-year-old and stayed for eighteen months to learn the craft of oil painting and its free application. Amiet’s artistic temperament as well as his direct style of painting and his lightness and aplomb made a great impression on Ernst. Following his academic studies with Eduard Stiefel at the Zurich University of the Arts and with Fritz Burger in Berlin, the time he spent painting in Cuno Amiet’s company came as a relief. At last he was able to resolve his vocational indecision and decided to become a painter. His initial dependency on Amiet’s style—evident in the landscapes and representations he produced during his stay at Oschwand—quickly yielded to his own formulations in terms of theme and design. He found his way “from fabulating drawing to painting”4 and created his own artistic world. His encounter with Sasha von Sinner, who was six years younger and joined Cuno Amiet at Oschwand shortly after him for a year, was to be fateful.

Sasha, whose full name was Mary Madeleine Sascha, came from a Bernese family of patricians and she was born on the Schlössli estate»5 in 1893 at Schlösslistrasse 29 in Bern, as the youngest daughter of Eduard and Marie (Mary) von Sinner-Borchardt, where she grew up with three siblings.6

At 52 her father had married the 19-year-old daughter of Carl Wilhelm Borchardt, a Jewish mathematics professor from Berlin, but he died six months after Sasha’s birth. As a mother of four she became a widow at the age of 27. She had a large circle of friends, organised house concerts, and in 1905 began to study medicine—in 1915 she became the first Bernese woman to defend her doctoral thesis at the University of Bern. During this period her children were raised by nannies, which negatively affected Sasha’s elder sister Lily in particular; Sasha, however, rapidly gained self-confidence and independence. Lily described her sister as follows:

“It was in Sasha’s nature to be at peace with herself from the very beginning; disregarding everything around her, she made her own way and instinctively followed her inner voice. Mother’s intellectual and musical ‘fuss’ got on her nerves and she distanced herself from it. She lived in her fantasy games, took care of her animals, dressed up her dolls, played with the model railway and climbed up chestnut trees. She painted and she drew.”7

Card sent by Sasha to her brother, undated.

The letters she wrote to her older brother Rudi, who died at a young age, were filled with illustrations and vignettes, and are revealing.8 The house concerts at the Engeried (Engestrasse 77), where the family had moved in 1899, were legendary:

“And so there were parties at our place at the Engeried: musical evenings of fabulous beauty to which I still think back and remember as being wonderful experiences! Sonatas, trios and quartets rang out into the mild summer evenings until late at night. Passers-by would stop on the Engestrasse and gladly listen.”9

Paul Klee in his studio in Bern, 1902. Photo from Sasha’s photo album, 1915.

Paul Klee often attended these concerts as a violinist. Even before his marriage in 1906 he had been introduced to the von Sinner household by his friend Dr Felix Lewandowsky, a dermatologist who was the same age as Klee. The two daughters, and especially Lily, adored the man who was eleven and fourteen years older than them, respectively.10 Klee quickly recognised young Sasha’s talent and persuaded her mother to let her leave the Gymnasium (grammar school), where she was the only girl in a classroom of boys; at the age of sixteen she went to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, where she studied drawing, sculpturing, painting and anatomy between 1909 and 1913. In 1914 Sasha von Sinner then joined Cuno Amiet in Oschwand for several months, where she met Ernst Morgenthaler; following this and upon Klee’s advice, she went to Munich in 1915/1916—where Morgenthaler also took painting classes with Klee. Sasha also went to the Hungarian Simon Hollósy’s school for painting, where she continued her anatomical studies. Nevertheless she also spent much time at Klee’s house. In this period Ernst Morgenthaler was deeply impressed by his conversations with Paul Klee and how they imparted “a plethora of inspirations”11, but also how Klee persuaded him to focus on his own initial, innocent work in which he had striven to capture his impressions directly on canvas. Ernst and Sasha enjoyed being together in distant Munich and gradually fell in love; in September 1916 they were wed in Burgdorf.

The personal and artistic connection to Cuno Amiet and Paul Klee thus formed the point of departure for their life together and was of great significance for both of them. The fresh couple first relocated to Geneva and then Hellsau, where Niklaus was born on 5 March, 1918. Their second son Fritz was born in Oberhofen on Lake Thun on 19 July, 1919, where the family had moved shortly before. They had learnt of Oberhofen from their friend, the sculptor Hermann Hubacher, and his wife, who spent their summer holidays there between 1916 and 1920.12

In order to devote herself to their growing family, and out of respect for her husband, whose style of painting was very close to her own, Sasha finally gave up painting.13 She supported Morgenthaler in his artistic endeavours and, in addition to raising their children and other family duties, she began to produce small sculptures and commercial artwork that was heavily influenced by Amiet’s teachings and her experience of Klee’s hand dolls, whose production she had witnessed and supported through sewing in Munich.

In 1922 she exhibited her impressive stuffed animals at the Society for the Arts in Wintherthur: artistic sculptures based on exceptional natural observations, accompanied by pictures by Hermann Hesse, Moissey Kogan, Ernst Morgenthaler, Emil Nolde and Niklaus Stoecklin. On 26 October, 1924, her third child Barbara was born.

For his part Morgenthaler enjoyed his first successes in the 1920s: in October 1918 he participated in the inaugural exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern and was able to sell all four of his paintings. In Bern he established new connections, in particular with the other artists at the Kunsthalle’s exhibition, and he participated in the lively cultural events at nearby Schloss Bremgarten. It was there that he met the musicians Othmar Schoeck and Fritz Brun as well as, most significantly, Hermann Hesse, with whom he formed a close friendship marked by a lifetime of exchanging letters;14 beyond this, there were further sculptors and painters, many of whom were from outside Bern:

“In 1918 industrialist Max Wassmer from Basel had settled at Schloss Bremgarten in Bern and made it into an open house for musicians (Othmar Schoeck, Fritz Brun), poets (Hesse as well as Hans Albrecht Moser, amongst others) and visual artists, whose work he promoted and supported—not as a professional ‘collector’ or ‘patron’ who handed out donations, but always and ever as a friend. In this way Bremgarten was the place in which new connections were made, old connections became stronger, and where French-Swiss artists Alexandre Blanchet, Eugène Martin and Henri Bischoff met Cuno Amiet, Louis Moilliet, Oscar Lüthy, Hermann Haller, Hermann Hubacher and Ernst Morgenthaler: this made Bern into the site of active cultural interaction in a better way than could have been accomplished through official initiatives.”15

This notwithstanding, Morgenthaler moved to Wollishofen on the edge of Zurich with his family in 1920. “Attracted by the artistic sense of disruption, there he met an actual exclave of ‘emigrated’ sculptors and painters from Bern: Karl Walser, Hermann Haller, Hermann Hubacher, Fritz Pauli, Oscar Lüthy, Werner Feuz and Otto Meyer-Amden, amongst others.”16

From this time onwards Morgenthaler began to have a more intense relationship with his cousin the writer Hans Morgenthaler (nicknamed Hamo), who was also friends with Hesse. It was Hesse who alerted him to their similarities: both of them were lonely and misunderstood, “needing to pierce their suffering which arose from a solid and seemingly insurmountable mountain of heritage and peasant and bourgeois traditions in order to find themselves. He [Hamo] did not adopt Ernst’s silent and secretive path, instead needing wild attempts and explosions […]. In comparison to his cousin the painter, Hamo appears as a pathological genius. When comparing the two, however, much relatedness and many similarities become evident. Both of them adopted the way of noble obstinacy, and both have developed compassion for human suffering that arises from their own suffering, and in particular compassion for the tribulations of outsiders and those who are unconventional.”17

The author Robert Walser was a guest at the Morgenthalers’ for a fortnight following a lecture in Zurich, where Hamo also met him. “I was very happy at your home last time, when Robert Walser and those others were visiting. I must certainly connect more with such people. I need this kind of inspiration,”18 he wrote to his cousin Ernst on 3 April, 1922.

In 1921 Morgenthaler made a portrait of the thirty-year-old author Emil Schibli, who at that time was working on his first novel: “Die innere Stimme. Geschichte eines Menschen in unserer Zeit” was published in 1923 and described his joyless childhood and harsh adolescence as Verdingbub (indentured child labourer). Due to his apprenticeship as a bookseller, he was able to visit the pedagogical seminary and he became a primary school teacher in Langnau, although he continued to write poetry.

His role model was Hesse and in his free time he made drawings and painted. He was connected with Morgenthaler through an affinity that became a life-long friendship characterised by extensive letter-writing and occasional meetings in other friends’ company.19

Sasha, drawn by Karl Geiser, around 1930.

In 1923 the Morgenthalers relocated once again, this time to Küsnacht. In this period Hermann Haller introduced Sasha and Ernst to the Bernese sculptor Karl Geiser, who had lived in Zurich since 1922.20 This fateful encounter was to threaten their marriage but it also provoked a new creative phase in Sasha. In addition to model figures, marionettes and figurines for exhibitions and fashion houses, she began to sew stuffed animals in particular for her own children because she regarded common toys as useless and too expensive. She later produced animal quartets and, from the 1930s onwards, numerous hand-made dolls with individualistic facial expressions. Due to her fertile artistic discussions with Morgenthaler, whom she often observed as he produced his portraits, and due to her friendship with Geiser, in whose considerations on how to authentically convert figures into sculptures she enthusiastically participated, Sasha devised her ideas on how to imbue her dolls with the asymmetry that gives them their unique liveliness. She also emphasised that “working with him contributed immensely to forming my own social awareness.”21 Sasha also frequently helped sculptor-friends repair broken sculptures, thereby honing her plastic skills.

Niklaus (l.), Barbara and Fritz in the garden of Meudon (France).

In January 1928 Ernst and Sasha Morgenthaler travelled to Morocco for three months, a time that was to be of great importance to both of them—in Ernst’s case, particularly in regard to his work. In Morocco he produced brighter paintings that reflected a new sense of comprehending the use of colours. He employed fresh and strong colours in a light and planar manner, and his figures come alive due to their spontaneous and solid drawing—an emancipation in terms of design becomes evident. At times the almost transparent colour makes things seem to hover, due to the way in which it was applied fluidly in thin lines. After their return the couple decided on radical change and moved to France. In October 1928 they found a house in Meudon, which at that time was still a separate town south-west of Paris. After much preparation the family relocated there on 13 December, 1928. In addition to Sasha and Ernst themselves, this meant the ten-year-old Niklaus, nine-year-old Fritz and four-year-old Barbara, who now changed not only school but also country and language—a fate typical for artists’ children. In Barbara’s words: “In Paris we had a spacious house with a large garden. The boys played at being Red Indians, and Mother would make teepees for them and dress them up in feather decorations. The neighbourhood children would stand at the garden gate and gawk. And then they would join in.”22 And Niklaus later told how they learnt French from the Swiss painter Werner Hartmann (who had lived in Paris since 1923) while they went for walks together and read advertising slogans on posters and shops.23 By visiting exhibitions at galleries and museums, Morgenthaler came into contact with the work of contemporary French artists, although he felt spiritually most attracted to the group of painters who worked with objects and tackled questions of pictoriality. This group included the afore-mentioned painter Hartmann, a friend who took him along to the artist cafes in Montparnasse and introduced him to his colleagues.24 Generally speaking it was largely due to Hartmann that French painting culture was made known in Switzerland through conversations, his own exhibitions and those of his painter friends.25

In 1932 the Morgenthalers returned to Switzerland and Zurich-Höngg and they moved into a studio house newly designed by the architect Hans Leuzinger in the Limmattalstrasse. Once everything had been installed, Sasha decided to go to Basel to study midwifery for a year. She organised family life by means of letters and orders to her housekeeper. After 1935 she worked as a midwife for several years: “I have seen over 1000 children come into this world, and this later contributed to my doll-making.”26

It was her love for children that also led her into humanitarian work: in 1940 she participated in establishing the so-called Hülfstrupps (aid troops) of the Swiss Women’s Civil Aid Service and in the end became the supervisor of all Hülfstrupp organisations. “When refugee children started streaming into Switzerland after the beginning of the war, I accompanied them as they were transported from the French border to the Swiss hinterland. I needed to overcome the many impressions and unforgettable experiences. They became the source of my first dolls.”27

In 1945 she was awarded the first prize at a Swiss toy competition.

In his paintings from the 1930s and 1940s Morgenthaler achieved a heightened and more subtle way of using colour in landscape paintings, thereby continuing a process he had begun under Amiet’s tutelage and honed in the environment of French painting culture. In the meanwhile he was also preoccupied with completing commissioned portraits. He often painted children, depicting them as lively and fragile in their life-worlds, their dreams and sense of security. In terms of design and intent, these paintings ideally complemented Sasha’s artistic dolls. In Zurich Morgenthaler returned to his customary social life and frequented Othmar Schoeck’s Saturday meetings at the Bünderstube, along with various friends such as Wilfried Buchmann, Johann von Tscharner, Hermann Haller and Hermann Hubacher. Often they would move on to Morgenthaler’s studio house in Höngg after closing time at the taverns, and Schoeck would sit at the piano and improvise music until dawn.28 At times they also went to Hermann and Annie Hubacher’s similarly welcoming domicile.

From the 1930s onwards, a further societal meeting point in Zurich played a role in enhancing these friendships: every month Albert Friedrich Meyerhofer, a manufacturer who had helped Morgenthaler with the construction of his house, organised a Tischgesellschaft (table community) and invited various artists, such as the writer Emil Schibli, the painter Johann von Tscharner, sculptors Hermann Hubacher and Otto Charles Bänninger, Othmar Schoeck as well as Oskar Reinhart and the banker Hans E. Mayenfisch. Hermann Hesse would attend when he was in Zurich, as occasionally did Karl Geiser, who would contribute to passionate debate “by vociferously defending his ‘communist’ position vis-a-vis Meyerhofer’s ‘capitalist’ ideology. It was due to Meyerhofer’s boundless generosity and his trust in Geiser’s wholesome character that such discussions took place without lasting dissonance.”29

Ernst Morgenthaler (l.) and Karl Geiser beneath a picture by Felix Valloton. 1940s.

Meyerhofer also founded a bowling club with the intention of bringing together artists, writers and art aficionados on such boisterous evenings. This group included Morgenthaler, von Tscharner, Hubacher, Geiser and Walter Sautter (one of Morgenthaler’s pupils). “The club called itself KKK (Künstler, Kommunisten, Kapitalisten—artists, communists, capitalists). There was much laughter and mockery.”30 Morgenthaler always spoke up for Geiser, both during the time he was closely involved with Sasha as well as after 1945, when Geiser and Sasha became estranged; in 1943 with the aid of Hubacher and Hesse, Morgenthaler succeeded in arranging for the industrialist Emil Bührle to pay Geiser a monthly stipend of 300 Swiss Francs.31

Ernst cultivated the same kind of close and friendly relationship with his brother, the academic apiarist Otto Morgenthaler, who was almost the same age as Ernst. Every year Otto sent him a jar of Hungg (honey) for his birthday, and one year the gift was accompanied by an affectionately moody letter that contained an ironical comparison: “Is not art also a form of canned industry? From a good as easily spoilt as is a spring dawn, you fashion a picture (or Hesse a poem, or Schoeck a song, and bees Hungg).”32

In 1943 Morgenthaler painted Josef Müller’s portrait in Solothurn, a man who had already commissioned a painting from him in 192133 and who had become a dear friend. Müller was initially a merchant and art collector, yet himself had begun to paint and was a pupil of Amiet’s for a period of time. He had a studio in Geneva and, later, in Paris.

Ernst Morgenthaler paints Josef Müller, 1943.

Müller provided Morgenthaler with the use of his studio on the Boulevard de Montparnasse 83 when Morgenthaler visited him; later he rented it out to Werner Hartmann. In 1943 he became the curator of the Art Museum in Solothurn and organised a large Morgenthaler exhibition there in 1945. Upon the occasion of a later visit at Müller’s, Morgenthaler proudly wrote to Sasha: “At Seppi’s place I slept in a room with 24 EM paintings.”34

In the same year of 1945, the Kunsthalle in Bern exhibited the entirety of Morgenthaler’s work. In his opening speech on 3 November, Amiet elegantly described the characteristics of his work: “He paints simply and directly, tone by tone, just as he saw them in nature. Every tone according to its form. And each one was influenced by its neighbour, and each was subjected to the whole in terms of form and value and colour.”35

On 23 November of the same year Amiet also wrote to Morgenthaler: “Yesterday I visited your exhibition three times and took another look at every single painting, every aquarelle and drawing. I simply have to tell you yet again: I am excited by every single piece. The way you invest in each stroke is fantastic and strange. As is the use of rare and always unexpected colours. And also each work’s contents and the way in which you provide it with a title by using figures or other elements.”36

Herman Hesse, painted by Ernst Morgenthaler.

1945 was also the year in which the Morgenthalers visited Hesse for six weeks in Montagnola, where Hesse declared his intention “to sit for (any kind of) portrait.” Morgenthaler made several portraits and paintings of Hesse while he sat as a model for him for 90 minutes each day. On Hesse’s birthday on 2 July Morgenthaler gave him one of the portraits as well as a stuffed hippopotamus made by Sasha. Over ten years later, in October 1959, Morgenthaler visited him again in Montagnola and made several further portraits of Hesse.

His painter colleague Walter Sautter, who was 24 years younger than him, recounted how generously Morgenthaler had involved Sautter in his work and circle of friends: “As a result of this he played a large role in my life for many years, in particular also because of his visits at the studio. I also visited him in Höngg. I was always intrigued by whatever he worked on, and that also influenced me greatly: watching how he worked. And I also met many colleagues at his place—Morgenthaler’s house was always a site of brisk va-et-vient (coming-and-going). For example I met the painter von Tscharner, and Geiser as well as other painters who occasionally dropped by, like Lauterburg from Bern. That’s how I became integrated into this group of painters.”37 On the topic of the Morgenthalers’ relationship, his wife Karin added: “That was very amusing. Sasha was of course always there, too, and they had their little arguments and differences of opinion, but it was a good atmosphere. One was always fully integrated. […] I think it was chiefly on Sunday afternoons that one visited the Morgenthalers. We were never alone then and there were always other people who joined.”

Walter Sautter continued: “They were both very headstrong and often came into hefty conflict with each other. And then there were these problems in their marriage. She had this intense relationship with Geiser, and he had affairs with my sister Gertrude and other women. Yet somehow everybody managed to get themselves together again and again.”

Between January 1951 and December 1953 Morgenthaler was the president of the Swiss Art Commission and invested himself in simplifying procedures and making jury decisions fairer. As soon as possible, however, he stepped down from his official role. In 1950 he made a portrait of Professor Wolfgang Pauli, the Nobel Prize winner in theoretical physics whom he had met in the 1940s and who had “massively impressed” him. He wrote to Hesse: “He’s also a great admirer of yours and recently asked me to tell you that he had nothing to do with the atomic bomb, and that he detests it and is sad about the abuse of research results.”38

Pauli and his wife Franca soon became friends with the Morgenthalers, and the two men would regularly play chess together. On the back of a postcard from Saint-Tropez Pauli wrote to Morgenthaler: “There are vendanges (grape harvests) here with many painters yet no chess players.”39 On 6 January, 1959 Morgenthaler wrote to his brother Otto: “The past year first took away Fis [Hans Fischer], then Schibli and now Pauli. One would never have suspected that the latter was such a famous man, especially not while playing chess.”40

Morgenthaler excelled at staging games of chess as an important ritual of friendship. Hesse wrote about how enjoyable playing chess with him was—Morgenthaler always let a less skilled opponent win, and would go on to explain which moves had resulted in victory. “In the end it was always the inexpert who won, and always under the illusion of having learnt something.”41

In Morgenthaler’s paintings of the 1950s new approaches can be detected. His late work (from about 1954 onwards) is characterised by an important simplification in terms of the motif and design in his paintings, even as his themes remain the same: details recede into the background, modelling often vanishes entirely and, both formally and in terms of colour, design becomes detached from nature. Splashes of colour structure the image and produce spatial effects. This structure of painting is liberated from linear bordering even while the painter clings to a hard, formal construction of the image. Some of his final paintings evince a tender and sometimes intense chromaticity, which is reduced to the most essential spaces and lines. This results in creating a poetic mood and forms a total lyrical statement: silent pictures that concentrate only on their central essence.

In the meanwhile Sasha had become very successful in Switzerland and internationally with her dolls, all of which she made individually and by hand. She employed a team of women who produced about 200 dolls annually that were delivered to the Heimatwerk in Bern and Zurich. Demand was great: once the delivery date just before Christmas became known, queues of buyers wanting to purchase one of the collectors’ dolls would form in front of the shop after midnight. To evade the accusation that she only made dolls for adults, she also went to great lengths to set up serial production of affordable children’s dolls.

Actor Heinrich Gretler (l.) and Ernst Morgenthaler with one of Sasha’s window-display dolls at the Swiss National Exhibition in Zurich, 1939.

During one of his visits to Paris, Ernst wrote to Sasha: “Haven’t you slipped into doing something you never wanted? There you are, dealing with the idiots at Jelmoli, F.C.W., Globus, etc., and your beautiful work is mingled and denigrated with these people’s kitsch. Is it worth it? And you’re falling apart over all the commissions and repairs. The dolls you make are so beautiful! If you had the peace and time for it, your imagination would produce hundreds more. Yet you have neither peace nor time—you’ve become a slave of your factory. In a couple of years’ time you’ll be so sick of it that you’ll have to give up. Don’t we want to think about doing something different today already, while we’re still healthy and hale […]?”42

Between December 1957 and April 1958 Ernst and Sasha went on a trip around the world, motivated by visiting their daughter Barbara, who had moved to Australia in 1956. From 1960 onwards they visited Sardinia several times after Sasha had persuaded Niklaus to build a house for them there.

After a protracted and severe illness, Ernst Morgenthaler died in Zurich on 7 September, 1962, almost exactly a month after his friend Hesse, who had been ten years older than him. After her husband’s death Sasha Morgenthaler continued to produce her dolls and travelled around the world another six times before she died on 18 February, 1975.

As a married artist couple the Morgenthalers were connected to each other through their differing backgrounds, formative childhood, similar education as well as similar views on art. Their family was important to both of them, as was their wide network of friends and colleagues, writers, art collectors, painters and sculptors with whom they discussed their lives and art at length. Juxtaposing Ernst and Sasha Morgenthalers’ statements, it is striking how closely they based their artistic work on similar notions—and how little they deviated from it over the course of their lives:

Ernst Morgenthaler paints a child, 1940s.

Ernst Morgenthaler focused on plain motifs derived from his personal environment and was, in essence, only able to paint things he had seen or experienced for himself or which moved him deeply. “Art is not derived from skill,” he would say, correcting a common adage, “but is present from the very beginning and is termed ‘emotionality’.”43

Sasha Morgenthaler invested personal elements into each of her creations—from the dreamy little girl dressed in white to the defiant rascal: facets of her rich life and her reservoir of conscious and subconscious energies. “The many impressions of people in distant countries are the material for the memories with which I work, for I can only give my dolls that which I have myself experienced.”44

Notes

1 Ernst Morgenthaler to Hermann Hesse, 20 June, 1952, as quoted in: Ernst Morgenthaler, Aufzeichnungen zu einer Geschichte meiner Jugend, with an Introduction by Hermann Hesse, Bern: Scherz 1957, p. 186. [Back to text]

2 Hermann Hesse, Ernst Morgenthaler, Zurich/Leipzig: Max Niehans 1936, p. 7. [Back to text]

3 Morgenthaler 1957 (see Note 1), p. 19. [Back to text]

4 Hesse 1936 (see Note 2), p. 20. [Back to text]

5 Contrary to common opinion, Sasha Morgenthaler-von Sinner did not in fact grow up at the country estate of Schloss Märchligen. The children did however regularly spend their summer holidays at the Campagne Märchligen whenever its owner (their aunt Charlotte Amalie Cécile Eden-von Sinner) went there from England, where she lived for the remainder of the year. She painted and water-coloured to her heart’s content and Sasha watched her for hours at a time. (Sasha Morgenthaler, typescript of a speech in Swiss German; date and occasion unknown; from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun.) [Back to text]

6 Rudolf (1887–1913), Curt (or Kurt) (1889–1977) and Lily (1890–1948). [Back to text]

7 Lily Löffler-von Sinner, Bild meiner Kindheit und Jugendzeit, 19 hand-written pages, undated (but prior to 1948), p. 5, from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. In her hand-written curriculum vitae Sasha wrote in 1974: “Depuis mon enfance j’ai eu l’intention de devenir sculpteur ou peintre ou sage femme!” [“Ever since my childhood I wanted to become a sculptor or painter or midwife.”], document, 3 pages, from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

8 Young Sasha’s letters and drawings from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

9 Löffler-von Sinner 1948 (see Note 7), p. 9a. [Back to text]

10 Lily von Sinner later noted: “Paul Klee was a wonderful violinist. I was in love with him and his masterful playing. Paul was so good to look at: he had incredibly small and well-built feet, and his hand was also small and beautiful; his whole shape was thin, delicate and handsome. His dark cherry-eyes were as beautiful as the curly beard on his chin and the hairline upon his clear forehead; when it rushed out of him, his laughter was uplifting—I liked everything about him. Surely I loved him deeply, but in the way a child loves: idolising, devoted, without any disquiet—and thus so intensely and incredibly beautifully!!” Löffler 1948 (see Note 7, p. 10). “One summer he brought along his wife, Lily Stumpf the pianist (who we thought was terribly ugly for a painter’s wife)” ibid., p 9a. [Back to text]

11 “At the time Paul Klee was not yet the celebrity he would later become. He was tolerant and generous and would lovingly pursue a matter that was far from him personally. […] Every Sunday morning Klee now came to visit, and the hours we spent together were filled with inspiration, making this the most valuable part of my time in Munich.” Morgenthaler 1957 (see Note 1), p. 69. [Back to text]

12 Stefan Biffiger, Ernst Morgenthaler. Leben und Werk, Bern: Benteli 1994, p. 145. [Back to text]

13 In an interview on 31 October, 1973, Sasha laconically answered a question about why she had not become a painter by saying: “In the company of my husband I painted poor Morgenthaler pictures.” Typescript from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. Elsewhere she said: “And soon I realised that painting was no longer possible. I saw everything the way he [Ernst] painted it, and I was a worse painter than him.” Typescript of a speech (event unknown) by Sasha Morgenthaler, 8 pages, from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

14 Ernst Morgenthaler to Hermann Hesse, 20 June, 1952: “For more than thirty years your work and friendship has been part of my life. I thank you for both. The things that have moved me over these years have often found their way into the letters I have written to you, and both laughter and tears are contained in equal measure.” As quoted in: Morgenthaler 1957 (see Note 1), p. 186. [Back to text]

15 Marcel Baumgartner, L’Art pour l’Aare. Bernische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert, Bern: Büchler 1984, pp. 148–150. [Back to text]

16 Josef Helfenstein,“Chronologie,” in: Der sanfte Trug des Berner Milieus. Künstler und Emigranten 1910–1920, exhibition catalogue, Josef Helfenstein and Hans Christoph von Travel (eds.), Bern: Kunstmuseum Bern 1988, p. 60. [Back to text]

17 Morgenthaler 1957 (see Note 1), p. 20. [Back to text]

18 Roger Perret (ed.), Der kuriose Dichter Hans Morgenthaler. Briefwechsel mit Ernst Morgenthaler und Hermann Hesse, Basel: Lenos 1983, p. 14. On Walser’s visit, see also: Ernst Morgenthaler, Ein Maler erzählt. Aufsätze, Reiseberichte, Briefe, with an Introduction by Hermann Hesse and illustrations by the editor, Zurich: Diogenes 1957, pp. 73–77. [Back to text]

19 Emil Schibli’s letters to Ernst Morgenthaler are in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

20 Jan Morgenthaler, Der Mann mit der Hand am Auge. Die Lebensgeschichte von Karl Geiser, Zurich: Limmat 1988, p. 49. [Back to text]

21 See Sasha Morgenthaler, exhibition catalogue of the Doll Museum Bärengasse in Zurich, with texts by Maria Netter and Sasha Morgenthaler as well as the biography penned by her children, Zurich [1976]. [Back to text]

22 Sasha Morgenthaler. Sasha-Puppen/Sasha Dolls, Steffan Biffiger (ed.), with contributions by Barbara Cameron Morgenthaler and Annemarie Monteil, Bern: Till Schaap 2014, p. 78f. [Back to text]

23 Personal communication by Niklaus Morgenthaler to Steffan Biffiger. [Back to text]

24 Personal communication and documents by Daniel Hartmann, Paris. [Back to text]

25 For more information, see www.wernerhartmann.ch. [Back to text]

26 Interview with Sasha Morgenthaler on 31 October, 1973, typescript in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

27 Ibid. [Back to text]

28 Morgenthaler, Maler, 1957 (see Note 18), pp. 85–87. [Back to text]

29 Ernst Morgenthaler to Sasha, 30 December, 1934, from the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun; see also Biffiger 1994 (see Note 12), p. 164. [Back to text]

30 Walter Sautter to Steffan Biffiger, 29 November, 1989, transcript in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

31 Biffiger 1994 (see Note 12), p. 172. [Back to text]

32 Otto Morgenthaler to Ernst, 10 December, 1943, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

33 Josef Müller to Ernst Morgenthaler, 29 July, 1922, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

34 Ernst Morgenthaler to Sasha, 20 July, 1954, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

35 Cuno Amiet, Die Freude meines Lebens. Prosa und Poesie, Stäfa: Rothenhäusler 1987, pp. 55–58. [Back to text]

36 Cuno Amiet to Ernst Morgenthaler, 23 November, 1945, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

37 Here and in the following: Walter Sautter and his wife Karin in conversation with Steffan Biffiger, Zumikon 27 November, 1989, transcript in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

38 Ernst Morgenthaler to Hermann Hesse, 21 October, 1950, as quoted in Morgenthaler 1957 (see Note 18), p. 181. Morgenthaler’s letters to Hesse are largely in possession of the German literature archive in Marbach. [Back to text]

39 Postcard from Wolfgang and Franca Pauli to Ernst and Sasha Morgenthaler, 14 September, 1948, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

40 Ernst Morgenthaler to Otto Morgenthaler, 6 January, 1959, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

41 Hermann Hesse, “Maler und Schriftsteller,” in: Biffiger 1994 (see Note 12), p. 193. [Back to text]

42 Ernst Morgenthaler to Sasha, 6 November, 1949, in possession of the Morgenthalers’ artistic estate in Thun. [Back to text]

43 Ernst Morgenthaler, “Begegnungen mit Bildern und Menschen,” in: Morgenthaler, Maler, 1957 (see Note 18), p. 57. Furthermore: “How else could it be that often we are so deeply moved by children’s drawings or the products of primitive peoples? As if we had heard the source of God rushing beforehand? Hasn’t an artist such as Paul Klee thrown out all of his ordinary skill so as to return to this source?” [Back to text]

44 Doll Museum at the Bärengasse 1976 (see Note 21). [Back to text]

Steffan Biffiger, MA (born 1952 in Naters, Switzerland). Studied art history and German literature in Fribourg. Editor and director of the Society for Swiss Art History in Bern, later editor-in-chief at Benteli Verlag in Bern. Since 2000 independent art critic, exhibitor and book designer, publicist-at-large, author of several monographs on artists, amongst others on Ernst Morgenthaler. Editor of “Sasha Morgenthaler. Sasha Puppen / Sasha Dolls,” Till Schaap Edition, Bern 2014. Artistic executor of the artistic estate of Ernst and Sasha Morgenthaler in Thun.